Daily Life | Disability | IBD | Ostomy

An image of the blog author a woman with brown hair in a hospital gown sitting upright in a hospital bed.

For as long as I remember, I felt as if my entire life rested on my ability to make being sick ok. My sister once observed how I always plaster a smile on my face regardless of my pain. I worked my entire life to cultivate that image, so the world could see me as smiling, happy, and healthy. I never wanted to admit to anyone, and most of all, myself, that I had a serious medical condition. It was even harder for me to accept that I met the definition of disabled based on the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The major life events of my adolescence and early twenties were colonoscopies, medication failures, and the development of Crohn’s Disease complications. When I was a teen, I was not worried about attending prom–I was worried about if I needed ostomy surgery. My fears about the new biologic medicine potentially causing cancer or how I would manage an NG feeding tube in a dorm room were nothing like what troubled my peers. Unfortunately, in adolescence (and sadly in society, in general), differences are not celebrated. So, over the years, to protect myself from feelings of aloneness, shame, and rejection, I started sugarcoating what it was to be sick.

When those in my life would ask me about a current symptom or problem that I was facing, I would provide an honest answer. However, for decades, I always ended these descriptions of hard realities with a qualifying statement about how it isn’t that bad. From surgeries to fistulas to stricture, I would always find a way to add a, “but it isn’t that bad because…” I sugarcoated what it was to be sick, downplaying the wars going on in my body because the one thing I hated more than anything was having people in my life treat me like I was just a sick person. I sugarcoated what it was to be sick because a guy I dated in college was concerned his stomach bug came from me. I sugarcoated what it was to be sick because I just wanted to live my life without my peers reminding me that my body was not the same healthy body they were fortunate enough to have; bodies that I honestly envied. The process of becoming disabled is not easy emotionally, and sugarcoating my illness took away some of the social troubles that come with having a difference.

Having limitations from nothing other than being unlucky enough to be born with an incurable disease is a hard pill to swallow. As the disease progressed and I started losing organs, managing my condition became progressively more challenging, and maintaining optimism, hope, and positivity became daily struggles. Then I crossed the invisible line that I had spent my entire life trying to avoid.

My dad’s last decade with Crohn’s disease was one of remission. Yet, he still struggled with daily symptoms and pain. During the later years of his life, it wasn’t Crohn’s Disease that gave him limitations– it was the damage his body sustained during his journey. For some IBD patients, the reality is that even if researchers discovered a cure for IBD today, it is too late– we are and will remain sick. The toll of multiple surgeries, chronic inflammation, and long-term medication side effects creates an invisible line where the damage becomes the problem more than the IBD. This reality was my dad’s, and in 2018 it became mine. It was during the process of recognizing that I had crossed that line and my body was no longer the same body it once was that I began to realize that no one gives you a medal for pushing yourself far beyond your limits. Growing up with a dad who was even more stubborn than me, I had been trained to “suck it up,” and to keep going, no matter what. It wasn’t until I became my dad that I realized how harmful these internalized messages had become.

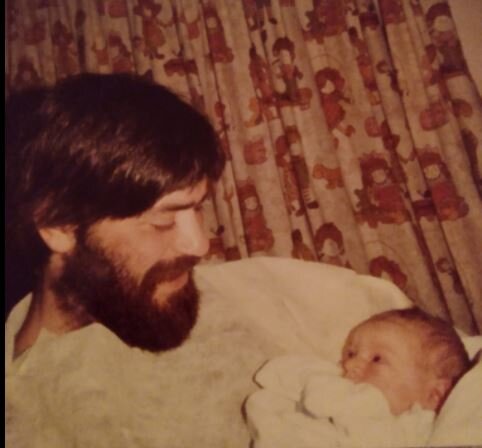

An image of the blog author as a baby being held by her dad who is seated.

My dad’s biggest struggle after he crossed that invisible line was bowel obstructions. During a bowel obstruction, the pain comes in waves. When obstructions progress, without medical intervention, a time comes when you begin to scream out at the peak of the pain, and there is nothing you can do to stop it. Rather than seeking medical attention at the ED, my dad prioritized work over caring for his body. I would hear him at night, moaning in pain, then he would self-irrigate and clear his obstruction, and the next day he would be off to build a house.

Like my dad, one of my IBD complications is bowel obstructions. And like my dad, for a long time, I prioritized work over taking care of my body. Until, there I was, with a bowel obstruction, on my hands and knees moaning in pain, not allowing myself the pain medicine my doctor prescribed to help me deal with obstructions. Before I could take care of the pain, I had to finish work. As the sounds emitting from my body started to become animalistic, I realized that I had heard those exact uncontrollable noises many times before from my dad. In an out-of-body experience, I could see myself curling my body up with each wave of pain, rocking back on my knees, stopping work, biting on a towel to not disturb the neighbors, refusing to take my medicine, and when the wave passed continuing to type. As I watched myself working in between the waves of pain it occurred to me- no one gives you a medal for putting yourself through hell. I knew something had to change. So, I finally consented to surgery, hoping that it would lead me back to remission and the ability to work without interruption.

Yet, that surgery left my body entirely changed. As I entered remission with more medical needs than I had during the flare, it became even harder for me to not drown in the unfairness of life. So, to not sink into a deep depression, I began to tell myself to focus on all the can and all the many ways my life has been positively impacted by that which I have never been able to control: my Crohn’s Disease. In other words, I didn’t just tell my friends, “but it isn’t that bad” I also told myself, “but isn’t that bad.” Yet, as I tried to do what I had always done to cope with IBD, I kept thinking of myself, on my hands and knees, howling in pain and torturing myself for a paycheck.

I knew that my post-surgical body couldn’t simultaneously live a full life and work. I knew that given the development of adhesion and the struggles to maintain hydration and nutrition that if I continued to say, “but it isn’t that bad” I would suffer. At that moment, I finally realized that I didn’t have to be my father’s daughter. As my brother told me, “everyone knows you are strong already– there is nothing more to prove.” More than anything though, I wanted a life that was more than being sick and recovering from work. I was tired of working from hospital rooms. I was tired of working through bowel obstructions. I was tired of trying to prove to everyone and myself that Crohn’s Disease “wasn’t that bad.”

Having to shed those unhealthy coping skills of “but it isn’t that bad” and to become honest about sick life through the process of entering remission as a disabled woman was not easy. However, learning how to own the identity of disabled has been the most transformative part of my almost three decades with Crohn’s Disease. Through the process of owning my disability, I was first brought to my knees, which led me to therapy and a life-changing ADHD diagnosis. Then I chose to create some meaning from crossing the invisible line and joined Girls With Guts, another life-changing event that has made me a much richer person. Then, through my work with GWG and therapy, I started gaining self-awareness and acceptance.

Now, after years of training myself to be a proud disabled woman, I can own the f- outta’ who I am: strong, capable, resilient, and sick. Disability pride, for me, is not hiding in the shadows and it is not having any shame that my life requires a bit of assistance. By the time my disability application was working its way to my day in court, I still found myself couching my answers with a “but it isn’t that bad because…” However, I have learned to stop myself as I try to cushion the blow and say, “it isn’t okay, it is hard, and it is not always easy.”

Through becoming disabled and owning disability as part of who I am, I have relearned the power in powerlessness, and even more, I have learned that I can be both ABLED and DISABLED. I know because, through these years of grief, loss, acceptance, and self-exploration, I am still here, I am still standing, and life is still damn good. In fact, life today is far better than those years of self-induced suffering trying to live in a disabled body without help, alone, hiding in shame, and trying to do everything that those with healthy bodies can.

What a powerful story! It’s eye opening to read about your struggle with Chrons and the impact of your dad’s illness on you. Thank you for sharing this, Jenny!