Many women with IBD are concerned about the impact that disease, medications, and surgery will have on their sexual health and intimacy. Unfortunately, there are several factors that can complicate sexual health for women with IBD including self-esteem and body image issues that relate to the physical changes due to having IBD. For example, prednisone-related weight changes or the presence of a recto-vaginal fistula can be both traumatic and impact self-esteem. However, even though there can be physical and emotional challenges related to sex and IBD, this does not mean that women with IBD cannot have a full and enjoyable sex life. Advocating for oneself, understanding the ways IBD impacts sex, and knowing about the available resources and treatments are critical to managing any potential problem or concern regarding sex and intimacy.

While many women with IBD do not have any sexual functioning complications from IBD, about 40-60% of women with IBD report some form of decreased sexual functioning. Some women experience significant sexual dysfunction from disease-related complications. Fistula, vaginal abscess, pelvic adhesions, bowel obstruction, pelvic surgery, and perianal stricture can severely impact female sexual functioning. In addition to these severe complications, in general, the research into sexual functioning and IBD states that anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and pain are associated with a decreased interest in sex and a decreased sexual satisfaction for women with IBD, more so than the presence of ostomy or IPAA (J-Pouch).

Disease Activity

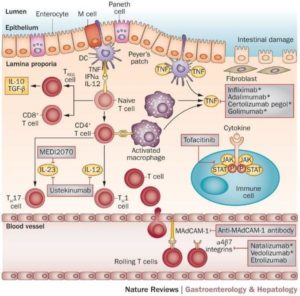

Active disease can decrease sexual interest and satisfaction for IBD patients. Thus, discussing disease state and how it impacts sexual functioning with one’s gastroenterologist is important. Additionally, depression and anxiety are key drivers of decreased sexual functioning in women with IBD; and patients with active disease are more likely to report more symptoms of anxiety and depression58. Developing and maintaining an IBD treatment plan to decrease disease activity is crucial in improving sexual functioning.

Depression and Anxiety

Treating active disease may help improve depression and anxiety. However, in addition to treating active IBD, addressing co-occurring anxiety and depression by obtaining mental health support via therapy and/or medication management may improve sexual desire. However, it is also important to note that in some instances selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (antidepressants) can also impair sexual functioning and can contribute to orgasmic and arousal disorders.

Severe Complications: Pain, Surgery Complications, Pelvic Floor Involvement.

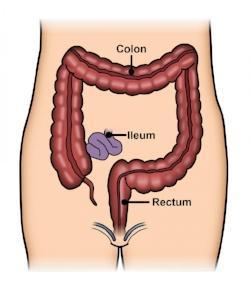

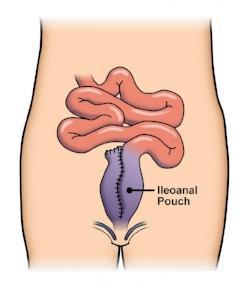

The pelvic floor muscles play a role in sexual functioning as well as bowel and bladder control. IBD symptoms of diarrhea, urgency, perianal pain, abdominal or pelvic pain, and draining can result in the pelvic floor muscles contracting as a protection method that can negatively impact sexual functioning. In other instances, pelvic surgery can create adhesions or scar tissue that results in pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Surgery can also result in injury to the sympathetic or parasympathetic nerve. For instance, after the creation of IPAA (J-Pouch), the risk of a sympathetic nerve injury resulting in decreased vaginal lubrication and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) may be as high as 38%. For women with proctocolectomy and ileostomy, 12% had painful intercourse before surgery, with 27% reporting the symptom post-surgery.

Treating sexual functioning symptoms such as increased vaginal dryness with lubrication and decreasing pain during intercourse via treatments such as pelvic floor physical therapy may improve sexual satisfaction, which may positively impact overall satisfaction. In addition to pelvic floor physical therapy, which is a treatment to manage pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, some patients may also find a referral to a urogynecologist or mental health provider critical to managing the physical and emotional symptoms of impaired sexual functioning.

Self-Image and Sexual Functioning

Studies have shown that about 75% of women with IBD and 81% of female IBD patients who have had surgery report issues with their body image60. Body image issues that can negatively impact sexual satisfaction seem to be affected by physical changes due to surgery, active disease symptoms, and the use of steroid medication61. Peer support and mental health referrals may improve impaired self-esteem and result in increased sexual functioning.

Vaginal Crohn’s Disease

A rare and underrecognized condition, Crohn’s disease of the vulva can occur in some women. Crohn’s disease of the vulva can result in lesions and inflammation. Discussing any vaginal symptoms with one’s medical team and controlling vulvar inflammation is important to decrease sexual functioning complications. In the presence of Crohn’s disease of the vulva, limiting surgical management of the disease is essential to preserve sexual functioning.

Medication Side Effects

Some medications are known to decrease sexual desire. For example, narcotics may decrease sexual desire and orgasm. In other instances, like steroids, side effects such as acne, weight gain, and increased facial hair can further negatively harm self-esteem and decrease sexual desire. Discussing sexual functioning concerns as they relate to medication management may help one’s physician to develop a treatment plan with medication that does not negatively affect one’s sexual health.

Receptive Anal Intercourse (RAI) Considerations

Women with IBD who engage in RAI (anal sex) may be at greater risk for STIs, anal dysplasia (abnormal cells within a tissue or organ), and intraepithelial neoplasia (abnormal cells on or in tissue that lines an organ).

STI

There is a greater risk of STIs (sexually transmitted infections) potentially due to inflammation compromising the integrity of the anorectal tissue63. It is important to discuss with one’s gastroenterologist or other medical providers anal sex because IBD and STI-related inflammation are often indistinguishable. Rectal STI testing may be necessary to determine the cause of inflammation.

Anal Dysplasia

An additional concern related to IBD and anal sex is an increased risk of anal dysplasia (pre-cancerous cells). Not only does anal sex increase the risk for anal dysplasia, so too does immunosuppression. Despite both anal sex and immunosuppression increasing the risk for anal dysplasia, there is not much research out there about anal dysplasia, anal sex, and women with IBD. However, prior research regarding cervical dysplasia shows that women with IBD have a higher rate of abnormal PAP smears. There is also an increased chance with those patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Therefore, some researchers hypothesize that there is an increased risk for anal dysplasia. While there are no specific recommendations related to screening for anal dysplasia, anal pap smears may be warranted for women with HIV-positive status, history of cervical or vulvar cancer, or other risk factors. Therefore, it is crucial for women who engage in anal sex to discuss these risks with their providers. Anal Sex Practices and IBD Some women who engage in anal sex use hygiene practices such as douching, laxative cleaners, or lubrication. While there are limited studies, they have shown that some practices such as using tap water or soap suds can damage the lining of the rectum. Thus, there is a theoretical possibility that these practices can trigger an IBD flare.

General Guidance

There have not been many studies on anal sex and IBD. Therefore, recommendations are not necessarily evidence based. However, the research to date suggests one should avoid anal sex while there is active inflammation or during a flare. Additionally, for those with IPAA (J-Pouch), the suture lines must heal before attempting anal sex, and adequate lubrication is encouraged. Due to some conflicting information regarding lubrication and the impact it can have on the lining of the rectum, it is generally preferred that IBD patients use silicone-based or water-based lubricants without using douching or enemas.

STD Prevention and Birth Control Considerations

Women with IBD are sometimes concerned about choosing a form of contraception that is effective and safe for them. While oral contraceptive pills are the most prescribed birth control option in the United States, for women with IBD, they may not be the best option67. Women with IBD have an increased chance of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, which is also a risk of oral contraception. In addition to these risks, oral contraception is absorbed primarily in the small bowel. Some women with Crohn’s have significant small bowel involvement or resection that may result in absorption issues. In addition to absorption, the relationships between oral contraceptives, IBD, and bone loss can be a concern for some women.

More concern about bone density and contraception is the relationship between the injection Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (aka Depo-Provera or “depo shot”) and bone loss. Therefore, for women with IBD who have osteoporosis or other bone density concerns, the depo shot may not be the best option. In contrast to oral contraceptives and the depo shot, longer-term contraception like the IUD and implants are generally recommended for women with IBD.

Menstruation and Birth Control

In addition to preventing unintended pregnancy, some women with IBD have found that contraceptives can decrease cyclical IBD symptoms related to menstruation. Menstruation has been determined to be linked to increasing IBD symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain. In general, Crohn’s disease patients tend to have more menstruation-related impacts than ulcerative colitis patients. One study determined that there was a reported 19% symptomatic improvement of these symptoms for women on estrogen-based contraception. For those with levonorgestrel IUDs, there was a 47% reported symptom improvement.