Celebrations | Food/Diet | IBD

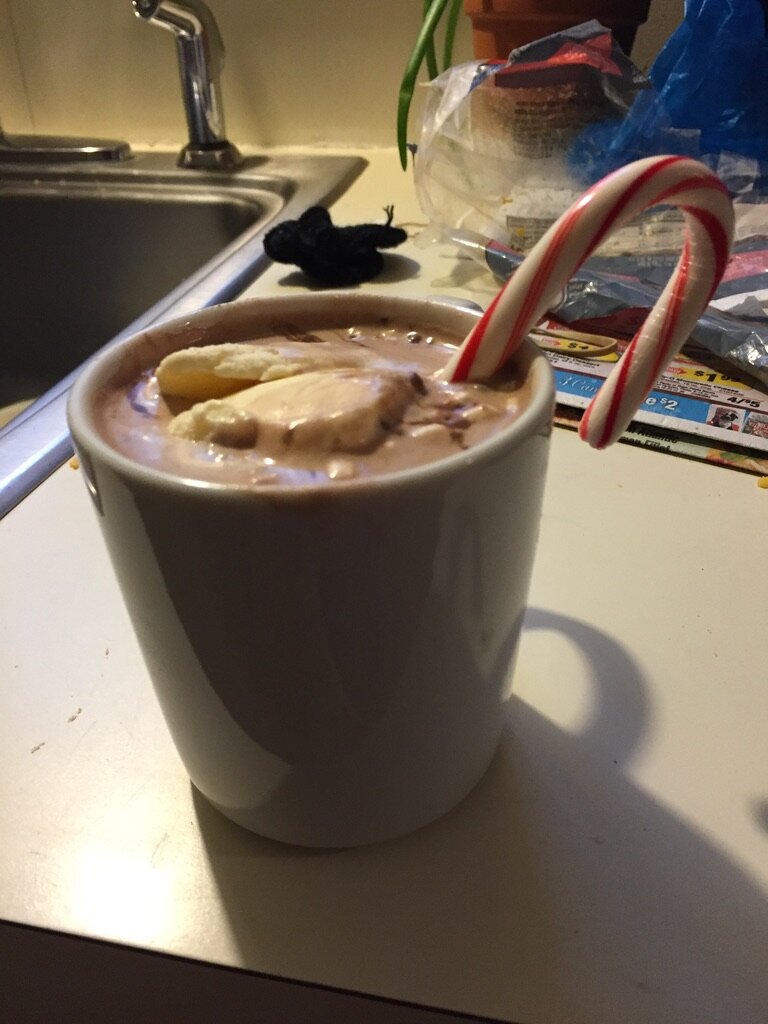

As a foodie, I always looked forward to a big holiday meal. It did not matter if it was turkey and mashed potatoes for Thanksgiving, a soufflé for New Year’s Day, or ham for Christmas; I was ready to dig in and eat! Of course, I often filled up on chips with chile dip and mini hotdogs before the ‘official’ meal began. I sat at my grandparents’ long dining room table filled but gluttonous. I needed to try everything. After consuming as much as my stomach allowed, I spent time relaxing and talking with my cousins before dessert, which has never been my favorite meal. Nevertheless, how can you turn down pumpkin pie on Thanksgiving or a hot cup of cocoa on a cold New Year’s night? I always left the house stuffed but was ready to have a midnight snack in a few hours: leftovers!

The joy of holiday feasting came to a crashing halt when I developed severe ulcerative colitis. I went from being able to eat anything and everything to being able to eat almost nothing. A few months after my diagnosis, I celebrated Thanksgiving at my grandfather’s house with chicken broth and a few bites of mashed potatoes. I had been in a severe flare-up for five months, and even these lighter foods triggered a stabbing sensation in my stomach. I put on my brave face for my family, especially my beloved grandfather, who kept offering me whatever he could and worrying about my rapidly decreasing weight. I ate all that I could and promised to eat more later.

When I got home that night, I let it all out, crying for what felt like the hundredth time. Thanksgiving was a feast holiday all about food (and family, of course!), and I could not even consume 50 calories of broth. The sight of other people eating and the scent of delicious foods that I thought I might never have again made me feel outcast and alone. This sense of isolation increased as I scrolled through social media seeing picture after picture of Thanksgiving plates full of turkey, stuffing, and mashed potatoes smothered in gravy. Would I ever have these luxuries again? Would I ever eat something with flavor and not feel as though I was being stabbed to death? Would I ever get to look forward to a meal? Would I ever feel normal? At the time, I did not know.

The weeks following Thanksgiving proved increasingly challenging. My body grew thinner and weaker as it continued denying the immunosuppressants and steroids pouring into it. The holiday season had officially begun, and there was food everywhere. Every social event seemed to be centered on food. I did not go to my Alma mater’s Holiday Party or Happy Hour, my graduate school’s caroling event, or my best friend’s party. I stayed home, drinking my electrolyte-infused water and reading. The excitement I used to feel when a professor brought food to class or the university library through a surprise pizza party transformed into dread. I hated having to turn down these treats while my mouth salivated, and my naive stomach groaned for food that would destroy my intestines. “You have to try the spinach dip,” I remember someone telling me at one of the few events I attended. I lied. I said I would try some later because I did not want to draw attention to myself or offend anyone. I put two crackers on my plate and picked them up every once in a while, so that people would think I was eating. I spent most of the time in the bathroom, partly because I was in a flare and needed to go but also because I needed to escape from the world of food where I did not belong.

I spent the next few holidays on limited diets. By the fourth of July, I was in the hospital on TPN and a clear liquid diet, begging my doctor to allow me some stained vegetable soup (a few steps up from the burnt broth I was receiving). Months of steroids and limited sleep transformed me into a stranger. I downplayed my symptoms, complained about hunger pain, and pleaded for my diet to be advanced. When my doctor told me that I would probably be on TPN for at least the next six weeks, I completely lost it. How could I ever go that long without my beloved food?! About a week and a half later, I was rushed to another hospital to have my colon removed. I cried with joy when I had my first real meal a few days later. The hospital’s mass-produced pancakes and eggs were so delicious that I momentarily forgot all of my pain. I still had a long road to recovery, but I could eat, and that is all that mattered to me at that moment.

I would like to say that I have grown since the day I broke down at the hospital. I could close my blog by describing how I learned to eat to live instead of living to eat. But this would be a weak cliche and a blatant lie. I still enjoy food and hate every restriction I have. I miss eating spicy food and binging on veggies without fear. Even though I am in remission, I have to scrutinize menus and watch what I eat at social events (which has not been much of a problem with COVID). I cannot always predict what food will settle well with me and what will not. I am still working to make peace with this new reality, but I have learned that this is all right. Some mountains take more time to climb. The only option I have is to keep going.