IBD | Information

An image of the author’s parents.

When I drove him to the Emergency Department, we both thought he would be going home that night. Some IV steroids, blood work, and a scan were warranted, but neither one of us thought it was anything more than a Crohn’s flare brought on by the death of his spouse of over thirty years. We did not believe that a few hours after entering the Emergency Department, a doctor would say the words, “we suspect cancer. His bowel is full of masses.” We also did not think that within 72 hours of walking in that my siblings and I would be authorizing the removal of life support for our sixty-year-old father. Sadly, by the time we got to the ER, my Dad had metastasized cancer throughout his body.

A short ten months prior, my dad’s routine colonoscopy was clear. At my urging, he had expressed to our doctor (we both had Crohn’s and were fortunate to see the same provider) that he had been having increased obstructions and weight loss. I also told our doctor at every visit I had that I was also worried about my dad. So, after the colonoscopy, my dad underwent an MR-enterography. The MR-enterography was also clear and only showed the extensive damage his body had endured from his lifetime of Crohn’s Disease. So, when that ER doctor mentioned the masses, we were both a bit shocked and scared. I started cursing my dad’s amazing surgeon who left that piece of colon he had, after all, I assumed, and he did too, that this was colon cancer.

The risks of colon cancer and IBD are well-documented, and we both knew that due to our Crohn’s, the risk was there. However, my family and I know now that it was likely not that piece of colon that led to my dad’s cancer. Instead, the pathology completed after his death showed that my dad’s death from septic shock was due to Adenocarcinoma likely originating in the small bowel. While it makes sense that, like the colon, inflammation in the small bowel can lead to the same turnover in the intestinal lining that increases the chances of irregularity that can cause cancer, I had never considered before my dad’s death that people with Crohn’s Disease are also at increased risk of small bowel cancers. Yet, for patients with Crohn’s Disease, the incidence of small bowel cancer is “almost as high as the well-established incidence of colorectal carcinoma in Crohn’s colitis[1].”

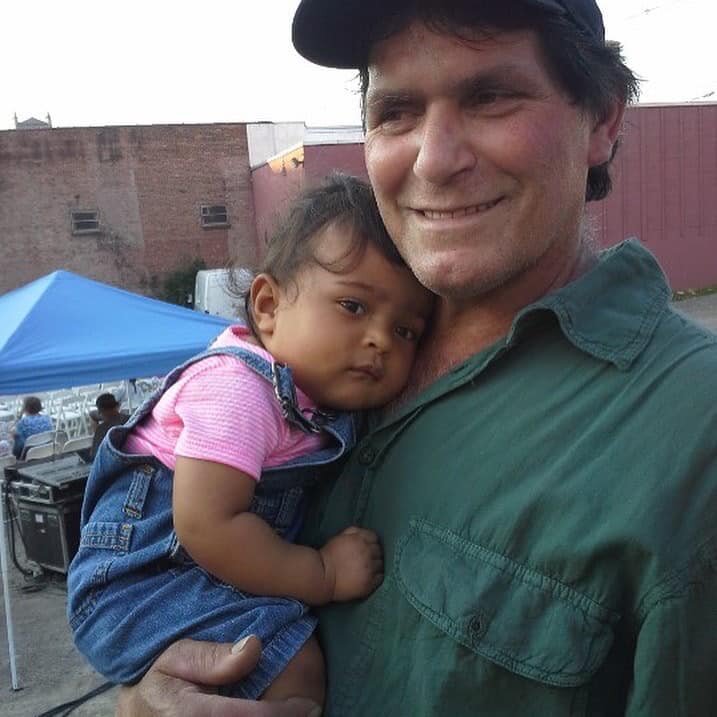

The author’s father holding his granddaughter.

Adenocarcinoma forms in the body’s mucus-secreting glands and glandular tissue. These glands are throughout the human body and are categorized into two types: exocrine and endocrine. As a result, Adenocarcinoma is responsible for many types of cancers. For instance, up to 80% of pancreatic cancer and 95% of colon and rectal cancers are Adenocarcinoma.

The literature on Adenocarcinoma originating in the small bowel and long-standing Crohn’s Disease is clear, “the risk of small bowel adenocarcinoma is higher in patients with Crohn’s disease than in the overall population[2].” In general, the risk of small bowel cancer is lower than that of colon cancer. However, for people with Crohn’s Disease, the risk of small bowel carcinoma is up to 60-fold of the general population’s risk. Most incidences of IBD-related small bowel cancers occur in individuals who have had extensive moderate-to-Severe disease activity[3], long duration of disease, younger age at diagnosis, strictures, bypassed loops of the small bowel, and the use of steroids and immunomodulators[4]. My Dad, sadly, met all these risk factors, having been diagnosed in his adolescence on 6MP for decades with moderate to severe fistulizing and stricturing disease.

One of the challenges related to small bowel cancer in the wake of long-standing Crohn’s disease is diagnostics. Unfortunately, small bowel cancer images are like images of strictures and active disease in patients who have Crohn’s[5][6]. Not only do images mimic Crohn’s, but the symptoms of small bowel adenocarcinoma also mimic the disease. One of the most common symptoms of small bowel cancer in Crohn’s disease is obstruction. In my dad’s case, obstructive symptoms were part of his ongoing Crohn’s management, and he had obstructions regularly since the 1990s. However, he had a period where he had fewer obstructions and improved quality of life. So, had we known that his symptoms combined with the findings; absence of active Crohn’s on scope, his scans, and within his blood work could all be indicative of small bowel carcinoma, we would have pushed harder for answers. Unfortunately, even had we pushed harder for answers, the reality is that the prognosis of small bowel carcinomas with Crohn’s disease has a fairly high mortality rate with two-year survival rates as low as 27%[7]. Despite these low odds of survival, knowing my Dad had small bowel cancer would have been a gift for my family to be able to say, “goodbye.”

Losing my dad to a complication of Crohn’s Disease has been one of the more challenging aspects of my own IBD journey. In the months after his passing, I read every article I could find in any medical journal about Crohn’s and small bowel Adenocarcinoma. I became an expert. Yet, no knowledge will bring my dad back or prevent me from developing cancer due to long-standing Crohn’s Disease. But I have learned, and I know things now that, had I known a year ago, would have made a significant difference and allowed my siblings and me to say goodbye. So, while I cannot bring my dad back, I can certainly share my knowledge and hopefully prevent other families from the shock we endured.

For more on how having a “Dad with Guts,” impacted Jenny’s journey check out: https://girlswithguts.wpengine.com/blog/2019/9/18/a-dad-with-guts.

[1] https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2009/10003/Small_Bowel_Cancer_in_Crohn_s_Disease__A_Case.1248.aspx

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124452/

[3] https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(17)30799-1/abstract

[4] https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/14/3/285/5804718

[5] https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/anticanres/33/7/2977.full.pdf

[6] https://www.hindawi.com/journals/crionm/2019/8473829/

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4155342/